library(GWASBrewer)

library(DiagrammeR)

library(dplyr)

#>

#> Attaching package: 'dplyr'

#> The following objects are masked from 'package:stats':

#>

#> filter, lag

#> The following objects are masked from 'package:base':

#>

#> intersect, setdiff, setequal, union

library(reshape2)

library(ggplot2)

set.seed(1)Introduction

This vignette demonstrates how to use the sim_mv

function to simulate data a few different types of GWAS data.

Introduction to sim_mv

The sim_mv function generates GWAS summary statistics

for multiple continuous traits from a linear structural equation model

encoded as a matrix of direct effects. Variants can be generated with or

without LD. There are also some helper functions for LD-pruning and

generating special kinds of direct effect matrices.

The sim_mv function internally calls a more general

function sim_lf which generates summary statistics given a

latent factor structure for a set of traits.

Throughout this vignette, we will use \(M\) to represent the number of traits and \(J\) to represent the number of variants.

Basic Usage

Input

The sim_mv function has five required arguments:

-

N: The GWAS sample size for each trait. This can be a scalar, vector, matrix, or data frame. If a vector,Nshould have length equal to \(M\). If there are overlapping samples between GWAS,Nshould be an \(M \times M\) matrix or data frame with format described in the “Sample Overlap” section below. -

J: The number of SNPs to simulate (scalar). -

h2: The heritability of each trait. This can be a scalar or a length \(M\) vector. -

pi: The proportion of SNPs that have a direct effect on each trait. This can be a scalar, a length \(M\) vector, or a matrix with \(J \times M\) matrix (more details on the matrix format can be found in the Effect Size Distribution vignette). -

G: A matrix specifying direct causal effects between traits.Gshould be an \(M\times M\) matrix described below. Alternatively, if there are no causal effects between any traits,Gcan be given as the positive integer \(M\). This is equivalent toG = matrix(0, nrow = M, ncol = M).

There are additional optional arguments:

-

R_EandR_obs: Alternative ways to specify environmental correlation (see “Sample Overlap” section below for more details). -

R_LD: A list of LD blocks (see “Simulating Data with LD”). -

af: Vector of allele frequencies (required ifR_LDis specified). IfR_LDis not specified,afcan be a scalar, vector of lengthJor a function (more details below). IfR_LDis specified,afmust be a vector with length corresponding to the size of the LD pattern (see “Simulating Data with LD”) -

sporadic_pleiotropy: Allow a single variant to have direct effects on multiple traits at random. Defaults toTRUE. -

pi_exact: IfTRUE, the number of direct effect SNPs for each trait will be exactly equal toround(pi*J). Defaults toFALSE. -

h2_exact: IfTRUE, the heritability of each trait will be exactlyh2. Defaults toFALSE. -

est_s: IfTRUE, return estimates ofse(beta_hat). Defaults toFALSEbut we generally recommend settingest_stoTRUEif you will be making use of standard errors. -

snp_effect_functionandsnp_infoare parameters useful for specifying non-default distributions of effect sizes. This is not covered in this vignette but is covered in the Effect Size Distributions vignette.

Output

The sim_mv function returns an object with class

sim_mv. This object contains the following elements:

GWAS summary statistics are contained in two or three matrices:

-

beta_hat: Simulated GWAS effect estimates and standard errors. -

se_beta_hat: True standard errors ofbeta_hat. -

s_estimate: Ifest_s= TRUEthen a simulated estimate ofse_beta_hat.

True marginal and joint, total and direct effects are contained in four matrices:

-

beta_joint: Total causal effects of SNPs on traits. -

beta_marg: Expected marginal association of SNPs on traits.beta_margis the expected value ofbeta_hat. When there is no LD,beta_margandbeta_jointare the same. -

direct_SNP_effects_joint: Direct causal effects of SNPs on traits. Direct means not mediated by other traits. -

direct_SNP_effects_marg: Likebeta_margbut considering only direct rather than total effects.

The relationship between traits is contained in two matrices:

-

direct_trait_effects: Matrix of direct effects between traits. This should be the same as the inputG. -

total_trait_effects: Matrix of total effects between traits.

Trait covariance is described by four matrices:

-

Sigma_G: Genetic variance-covariance matrix, determined by heritability andG. -

Sigma_E: Environmental variance-covariance matrix. This is determined by heritability andR_E. -

trait_corr: Population trait correlation, equal tocov2cor(Sigma_G + Sigma_E). For data produces withsim_mv, trait variance is always equal to 1, sotrait_corr = Sigma_G + Sigma_E. -

R: Correlation in sampling error ofbeta_hatacross traits, equal totrait_corrscaled by a matrix of sample overlap proportions.

Some other pieces of information useful in more complicated scenarios:

-

h2: Realized trait heritability. For data produced withsim_mv, this will always be equal todiag(Sigma_G). However this may not be the case for resampled data (see the Resampling Data vignette). -

pheno_sd: Standard deviation of traits. For data produced withsim_mv, this is always a vector of 1’s. -

snp_info: A data frame of variant information including allele frequency and possibly other information (see the Effect Distribution vignette). -

geno_scale: Equal toalleleif effect sizes are per allele orsdif effect sizes are per genotype SD (i.e. standardized).

The order of the columns of all results corresponds to the order of

traits in G.

Simplest Usage

The simplest thing to do with sim_mv is to generate

summary statistics for \(M\) traits

with no causal relationship with no LD between variants. In the code

below, we generate data for 3 traits and 100,000 variants. Since the

sample size is specified as a scalar, all three GWAS have the same

sample size but there are no overlapping samples. For some variety, we

give each trait a different heritability and a different proportion of

causal variants.

dat_simple <- sim_mv(G = 3, # using the shortcut for specifying unrelated traits.

# equivalent to G = matrix(0, nrow = 3, ncol = 3)

N = 50000, # sample size, same for all three traits

J = 100000, # number of variants

h2 = c(0.1, 0.25, 0.4), # heritability

pi = c(0.01, 0.005, 0.02), # proportion of causal variants

est_s = TRUE # generate standard error estimates.

)

#> SNP effects provided for 100000 SNPs and 3 traits.The sim_mv function always assumes that traits have been

scaled to have variance equal to 1, so effect sizes are interpretable as

the expected change in the trait in units of SD per either alternate

allele (if geno_scale = allele) or per genotype SD (if

geno_scale = sd). In our case,

dat_simple$geno_scale is equal to sd because

no allele frequencies were provided. The realized genetic and

environmental variance matrices are in Sigma_G and

Sigma_E.

dat_simple$Sigma_G

#> [,1] [,2] [,3]

#> [1,] 1.045339e-01 4.515705e-06 0.0005262836

#> [2,] 4.515705e-06 2.530663e-01 0.0009271551

#> [3,] 5.262836e-04 9.271551e-04 0.4429666631

dat_simple$Sigma_E

#> [,1] [,2] [,3]

#> [1,] 0.8954661 0.0000000 0.0000000

#> [2,] 0.0000000 0.7469337 0.0000000

#> [3,] 0.0000000 0.0000000 0.5570333The diagonal of dat_simple$Sigma_G is equal to the trait

heritability (also stored in dat_simple$h2). We can see

that these numbers are close to but not exactly equal to the values

input to the h2 parameter. This is because h2

provides the expected heritability. If we want to force the realized

heritability to be exactly equal to the input h2, we can

use h2_exact = TRUE. The genetic covariance (the

non-diagonal elements of Sigma_G) is slightly non-zero

because the traits share a small number of causal variants by chance. If

we want to prevent this, we can use

sporadic_pleiotropy=FALSE. However, in some cases, it is

not possible to satisfy sporadic_pleiotropy = FALSE and

that option will generate an error.

The simulated summary effect estimates are in

dat_simple$beta_hat and simulated standard error estimates

are in dat_simple$s_estimate. In our case, these will both

be 100,000 by 3 matrices.

head(dat_simple$beta_hat)

#> [,1] [,2] [,3]

#> [1,] 0.0063610849 -0.007271609 0.003926946

#> [2,] 0.0009913487 0.012587585 0.003931295

#> [3,] 0.0031938057 -0.002387450 -0.003170087

#> [4,] 0.0030629600 0.001481305 -0.002369274

#> [5,] 0.0020414224 0.007953421 0.005325885

#> [6,] 0.0030602370 -0.002037463 -0.008673129

head(dat_simple$s_estimate)

#> [,1] [,2] [,3]

#> [1,] 0.004478273 0.004480611 0.004483377

#> [2,] 0.004468891 0.004478611 0.004482622

#> [3,] 0.004472107 0.004466985 0.004465830

#> [4,] 0.004465952 0.004460529 0.004476516

#> [5,] 0.004449150 0.004493462 0.004482853

#> [6,] 0.004480817 0.004464715 0.004479402In actual GWAS data, these two matrices are the only information we

get to observe. Everything else stored in dat_simple is

information that is unobservable in “real” data but useful for

benchmarking analysis methods. The effect estimates in

dat_simple$beta_hat are always estimates of the true

marginal effects in in dat_simple$beta_marg. Since there is

no LD in this data, marginal and joint effects are the same, so you will

find that dat_simple$beta_marg and

dat_simple$beta_joint are identical. We can identify causal

variants as variants with non-zero values of beta_joint.

For example, which(dat_simple$beta_joint[,1] != 0) would

give the indices of variants causal for trait 1.

The estimates in dat_simple$s_estimate are estimates of the

standard error of dat_simple$beta_hat. The true standard

errors are stored in dat_simple$se_beta_hat. If we had left

est_s at its default value of FALSE,

dat_simple would not contain the s_estimate

matrix.

Specifying Causal Relationships Between Traits

The matrix G specifies a linear structural equation

model for a set of traits. To generate a set of \(M\) traits with no causal relationships,

G can be set either equal to M or to an \(M\times M\) matrix of 0’s. Otherwise,

G must be an \(M \times

M\) matrix with G[i,j] specifying the direct linear

effect of trait \(i\) on trait \(j\). The diagonal entries of \(G\) should be 0 (no self effects). An error

will be generated if G specifies a graph that contains

cycles. Since all traits have variance equal to 1, so

G[i,j]^2 is the proportion of trait \(j\) variance explained by the direct effect

of trait \(i\).

For example, the matrix

G <- matrix(c(0, sqrt(0.25), 0, sqrt(0.15),

0, 0, 0, sqrt(0.1),

sqrt(0.2), 0, 0, -sqrt(0.3),

0, 0, 0, 0), nrow = 4, byrow = TRUE)

colnames(G) <- row.names(G) <- c("X", "Y", "Z", "W")

G

#> X Y Z W

#> X 0.0000000 0.5 0 0.3872983

#> Y 0.0000000 0.0 0 0.3162278

#> Z 0.4472136 0.0 0 -0.5477226

#> W 0.0000000 0.0 0 0.0000000corresponds to the graph

To simulate simple data from this graph, we can use

sim_dat1 <- sim_mv(G = G,

N = 50000,

J = 100000,

h2 = c(0.3, 0.3, 0.5, 0.4),

pi = 0.01,

est_s = TRUE)

#> SNP effects provided for 100000 SNPs and 4 traits.In this specification, we have four GWAS with sample size 50,000,

again with no overlapping samples. Since J = 100000 and

pi = 0.01, we expect each trait to have 1000 direct effect

variants.

With causal relationships between traits, there are now some interesting things to notice about the output. First, we can see that there is both genetic and environmental covariance between the traits.

sim_dat1$Sigma_G

#> X Y Z W

#> X 0.28249614 0.14135064 0.2179663 0.03485498

#> Y 0.14135064 0.29912608 0.1089297 0.08886324

#> Z 0.21796635 0.10892974 0.4892269 -0.14942217

#> W 0.03485498 0.08886324 -0.1494222 0.40289524

sim_dat1$Sigma_E

#> X Y Z W

#> X 0.7175039 0.3545701 0.2288111 0.2619020

#> Y 0.3545701 0.7008739 0.1130720 0.2951464

#> Z 0.2288111 0.1130720 0.5107731 -0.1531603

#> W 0.2619020 0.2951464 -0.1531603 0.5971048

sim_dat1$trait_corr

#> X Y Z W

#> X 1.0000000 0.4959207 0.4467774 0.2967570

#> Y 0.4959207 1.0000000 0.2220017 0.3840097

#> Z 0.4467774 0.2220017 1.0000000 -0.3025824

#> W 0.2967570 0.3840097 -0.3025824 1.0000000By default, sim_mv assumes that direct environmental

components of each trait are independent, meaning that the DAG explains

all of the correlation between traits. This is modifiable using the

R_E and R_obs arguments, discussed a bit later

in this vignette.

Relationships between traits are described by two matrices,

direct_trait_effects which is equal to the input

G matrix and total_trait_effects which gives

the total effect of each trait on each other trait. Here we can notice

that the direct effect of \(Z\) on

\(W\) is -0.548 as specified but the

total effect includes the effects mediated by \(X\) and \(Y\) as well, \(-0.548 + 0.447\cdot 0.387 + 0.447\cdot 0.5 \cdot

0.316 = -0.304\).

sim_dat1$direct_trait_effects

#> X Y Z W

#> X 0.0000000 0.5 0 0.3872983

#> Y 0.0000000 0.0 0 0.3162278

#> Z 0.4472136 0.0 0 -0.5477226

#> W 0.0000000 0.0 0 0.0000000

sim_dat1$total_trait_effects

#> X Y Z W

#> X 0.0000000 0.5000000 0 0.5454122

#> Y 0.0000000 0.0000000 0 0.3162278

#> Z 0.4472136 0.2236068 0 -0.3038068

#> W 0.0000000 0.0000000 0 0.0000000We can also use the output to understand which variants have direct

effects on each trait and which have indirect (mediated) effects. The

direct_SNP_effects_joint object gives the direct effect of

each variant on each trait while beta_joint gives the the

total effect of each variant. Direct and total marginal effects are

stored in direct_SNP_effects_marg and

beta_marg. Since we again have no LD, the

_marg and _joint matrices are the same.

Direct SNP effects are always independent across traits while total SNP effects are the sum of direct effects and indirect effects mediated by other traits. We will make some plots to see the difference.

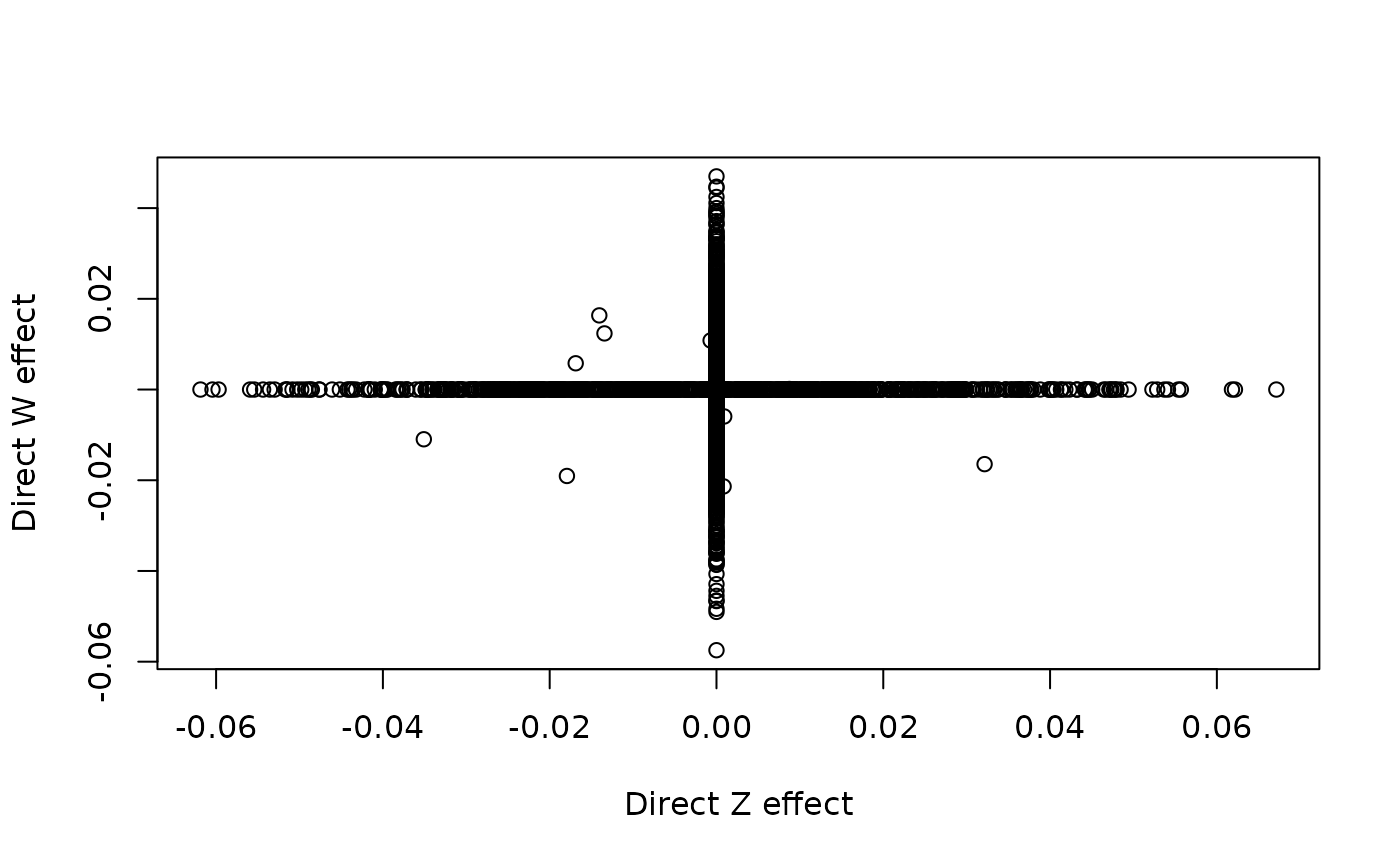

First we plot direct SNP effects on \(Z\) vs direct SNP effects on \(W\)

plot(sim_dat1$direct_SNP_effects_joint[,3], sim_dat1$direct_SNP_effects_joint[,4],

xlab = "Direct Z effect", ylab = "Direct W effect")

Most variants have direct effects on at most one of \(Z\) or \(W\) but a small number affect both because

sporadic_pleiotropy = TRUE by default.

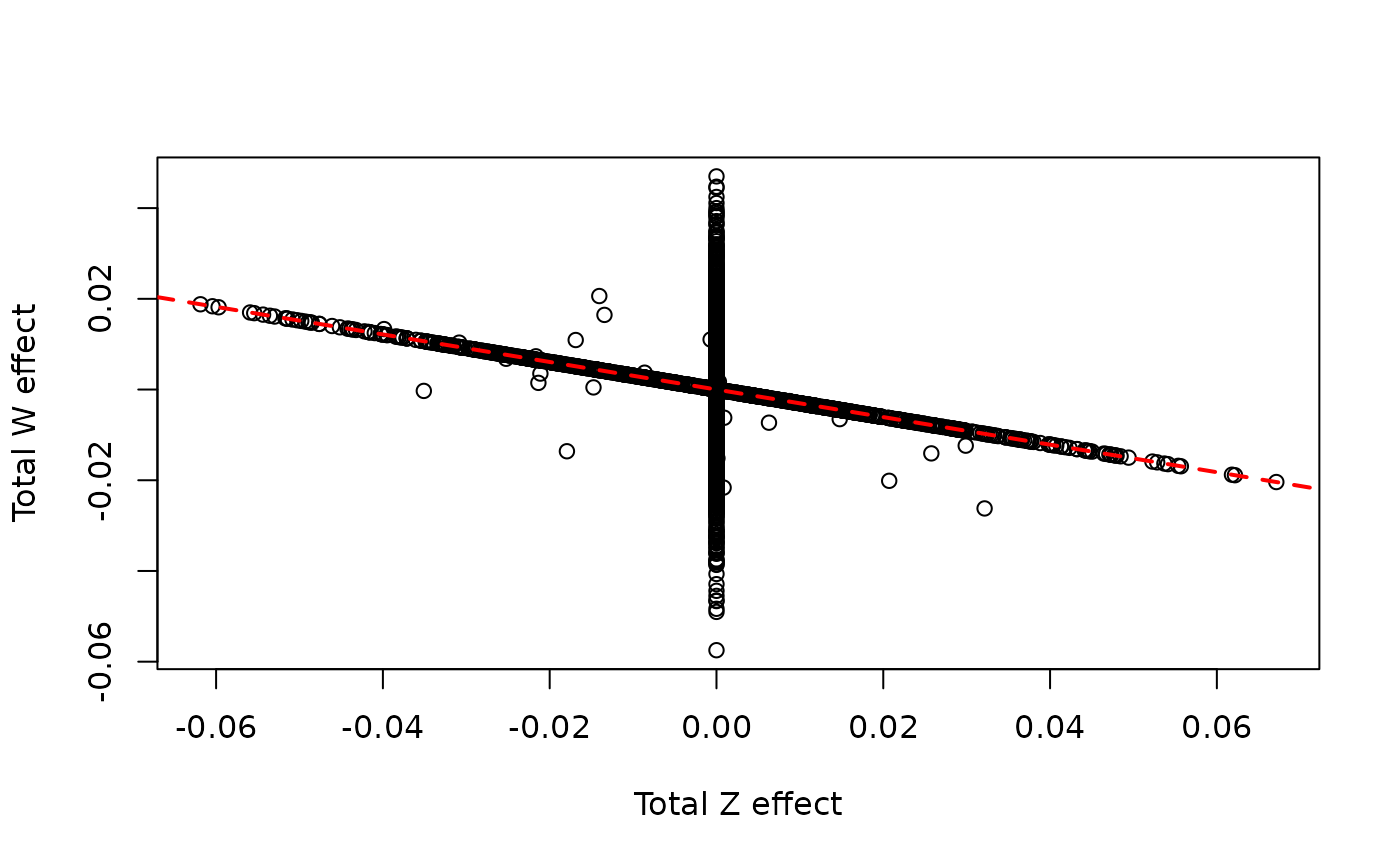

Next we plot the total SNP effects on \(Z\) vs the total SNP effects on \(W\). Because \(Z\) has a causal effect on \(W\), all variants with effects on \(Z\) also affect \(W\). The line in the plot has slope equal

to the total effect of \(Z\) on \(W\). The majority of SNPs that have

non-zero effect on \(Z\) fall exactly

on this line. With sporadic_pleiotropy= FALSE, all of the

variants with non-zero effect on \(Z\)

would fall on this line. The variants on the vertical line at 0 are

variants with non-zero direct effect on \(W\) but no direct effect on \(Z\).

plot(sim_dat1$beta_joint[,3], sim_dat1$beta_joint[,4],

xlab = "Total Z effect", ylab = "Total W effect")

abline(0, sim_dat1$total_trait_effects[3,4], col = "red", lty = 2, lwd = 2)

Specifying Allele Frequencies

Allele frequencies can be specified using the af

argument which can accept a scalar, a vector of length \(J\), or a function that takes a single

argument and returns a vector of allele frequencies with length

determined by the argument. If af is a scalar, the same

allele frequency is used for all variants. The function specification is

used in the example below. If the af argument is provided,

sim_mv will return all results on the per-allele scale and

the geno_scale element of the returned object will be equal

to allele. The snp_info element of the

returned object will also include the allele frequency of each

variant.

sim_dat2 <- sim_mv(G = G,

N = 50000,

J = 10000,

h2 = c(0.3, 0.3, 0.5, 0.4),

pi = 0.01,

af = function(n){rbeta(n, 1, 5)})

#> SNP effects provided for 10000 SNPs and 4 traits.

sim_dat2$geno_scale

#> [1] "allele"

head(sim_dat2$snp_info)

#> SNP AF

#> 1 1 0.05448172

#> 2 2 0.52558863

#> 3 3 0.02522715

#> 4 4 0.29653930

#> 5 5 0.29400173

#> 6 6 0.09964018Simulating Data with LD

The sim_mv function can be used to generate data with LD

by inputting a list of LD matrices and corresponding allele frequency

information. The function will work fastest if the LD matrix is broken

into smallish independent blocks. The input data format for the LD

pattern is a list of either a) matrices, b) sparse matrices (class

dsCMatrix) or c) eigen decompositions (class

eigen). R_LD is interpreted as providing

blocks in a block-diagonal SNP correlation matrix.

Importantly, the supplied LD pattern does not have to be the same

size as the number of SNPs we wish to generate (J). It will

be repeated or subsetted as necessary to create an LD pattern of the

appropriate size.

The package contains a built-in data set containing the LD pattern from Chromosome 19 in HapMap3 broken into 39 blocks. This LD pattern was estimated from the HapMap3 European subset using LDShrink. This data set can also be downloaded here. The LD pattern must be accompanied by a vector of allele frequencies with length equal to the total size of the LD pattern (i.e. the sum of the size of each block in the list).

Let’s look at the built-in LD data

data("ld_mat_list")

data("AF")

length(ld_mat_list)

#> [1] 39

sapply(ld_mat_list, class)

#> [1] "dsCMatrix" "dsCMatrix" "dsCMatrix" "dsCMatrix" "dsCMatrix" "dsCMatrix"

#> [7] "dsCMatrix" "dsCMatrix" "dsCMatrix" "dsCMatrix" "dsCMatrix" "dsCMatrix"

#> [13] "dsCMatrix" "dsCMatrix" "dsCMatrix" "dsCMatrix" "dsCMatrix" "dsCMatrix"

#> [19] "dsCMatrix" "dsCMatrix" "dsCMatrix" "dsCMatrix" "dsCMatrix" "dsCMatrix"

#> [25] "dsCMatrix" "dsCMatrix" "dsCMatrix" "dsCMatrix" "dsCMatrix" "dsCMatrix"

#> [31] "dsCMatrix" "dsCMatrix" "dsCMatrix" "dsCMatrix" "dsCMatrix" "dsCMatrix"

#> [37] "dsCMatrix" "dsCMatrix" "dsCMatrix"

# This prints the number of SNPs in each block

sapply(ld_mat_list, nrow)

#> [1] 140 519 339 435 523 280 675 325 651 548 274 483 442 744 460 177 469 173 358

#> [20] 564 392 737 596 818 307 863 276 435 204 364 480 381 757 844 753 656 483 856

#> [39] 709

sapply(ld_mat_list, nrow) %>% sum()

#> [1] 19490

length(AF)

#> [1] 19490The LD pattern covers 19,490 SNPs, equal to the length of the

AF vector. The built-in LD pattern corresponds to a density

of about 1.2 million variants per genome. However, for this example, we

will generate data for only 100k variants. This means that causal

effects will be denser than they might be in more realistic data with

the same number of effect variants.

set.seed(10)

sim_dat1_LD <- sim_mv(G = G,

J = 1e5,

N = 50000,

h2 = c(0.3, 0.3, 0.5, 0.4),

pi = 0.01,

R_LD = ld_mat_list,

af = AF)

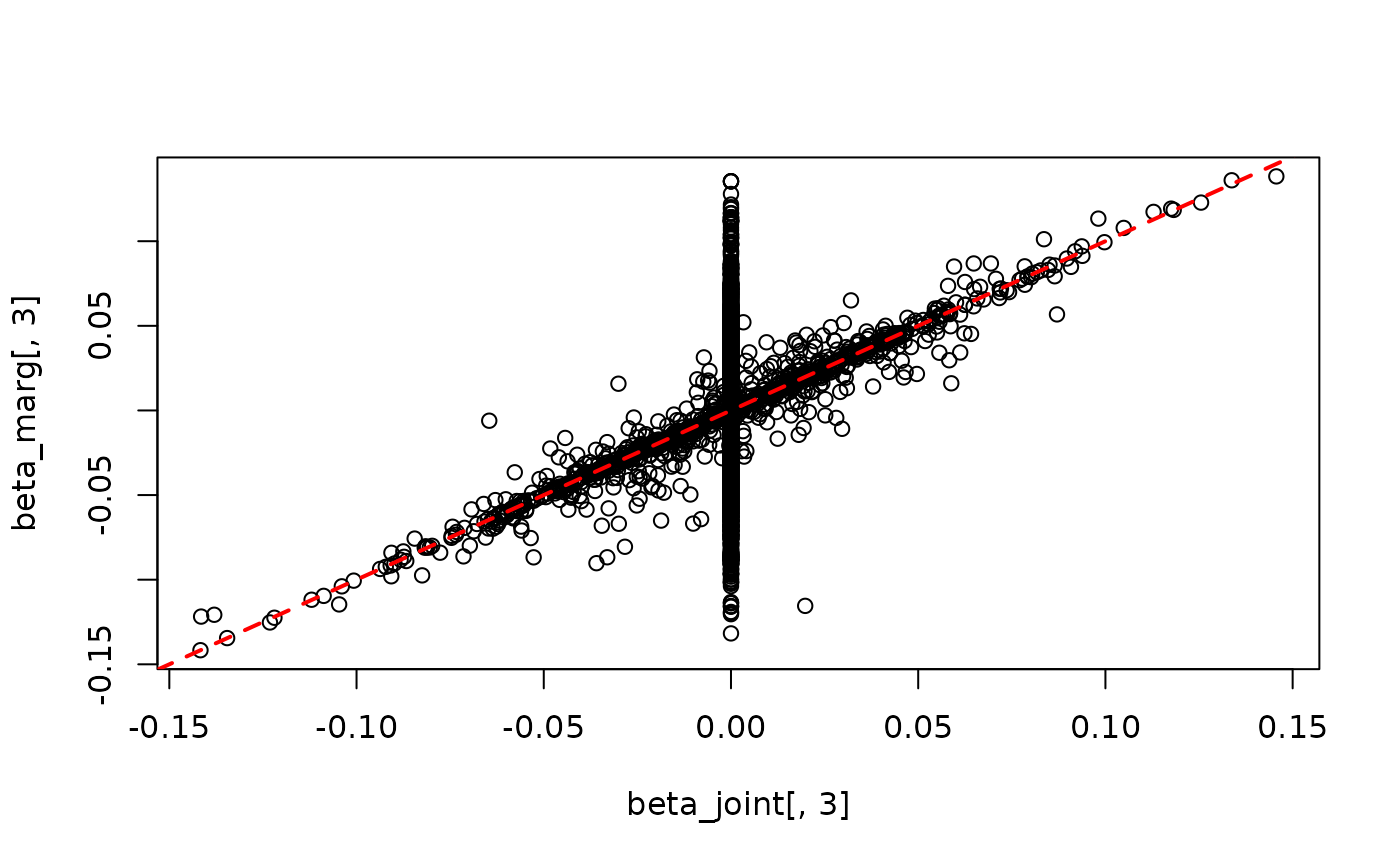

#> SNP effects provided for 100000 SNPs and 4 traits.In data with LD, the _joint objects and

_marg objects are not identical. For example, we can

compare beta_joint and beta_marg for the third

trait (\(Z\)).

Variants with non-zero values of beta_joint[,3] have

causal effects on \(Z\) while those

with non-zero values of beta_marg[,3] have non-zero

marginal association with \(Z\),

meaning that they are in LD with at least one causal variant. In the

plot, we see that many variants with no causal effect have non-zero

marginal association, which is expected. The causal variants don’t fall

exactly on the red line because, multiple causal variants may fall into

the same LD block.

LD-Pruning, LD-Proxies, and LD Matrix Extraction

Many post-GWAS applications such as Mendelian randomization and

polygenic risk score construction require an LD-pruned set of variants.

GWASBrewer contains a few LD-related functions to help with

pruning and testing methods that require input LD matrices. Note that

all of these methods use the true LD pattern rather than estimated

LD.

The sim_ld_prune function will perform LD-clumping on

simulated data, prioritizing variants according to a supplied

pvalue vector. Although this argument is called

pvalue, it can be any numeric vector used to prioritize

variants. The pvalue argument can also accept an integer.

If pvalue = i, variants will be prioritized according to

the p-value for the ith trait in the simulated data. If

pvalue is omitted, variants will be prioritized randomly

(so a different result will be obtained each re-run unless a seed is

set).

To speed up performance, if you only need variants with \(p\)-value less than a certain threshold,

supply the pvalue_thresh argument. Below we prune based on

the p-values for trait \(Z\) in two

equivalent ways.

pruned_set1 <- sim_ld_prune(dat = sim_dat1_LD,

pvalue = 3,

R_LD = ld_mat_list,

r2_thresh = 0.1,

pval_thresh = 1e-6)

#> Prioritizing variants based on p-value for trait 3

length(pruned_set1)

#> [1] 354

pval3 <- with(sim_dat1_LD, 2*pnorm(-abs(beta_hat[,3]/se_beta_hat[,3])))

pruned_set2 <- sim_ld_prune(dat = sim_dat1_LD,

pvalue = pval3,

R_LD = ld_mat_list,

r2_thresh = 0.1,

pval_thresh = 1e-6)

all.equal(pruned_set1, pruned_set2)

#> [1] TRUEsim_ld_prune returns a vector of indices corresponding

to an LD-pruned set of variants.

The sim_ld_proxy function will return indices of

LD-proxies (variants with LD above a given threshold) with a supplied

set of variants. Here we extract proxies for a few arbitrary variants.

The return_mat option will cause the function to return the

LD matrix for the proxies as well as the indices of proxies

ld_proxies <- sim_ld_proxy(sim_dat1_LD, index = c(100, 400, 600), R_LD = ld_mat_list, r2_thresh = 0.64, return_mat = TRUE)

ld_proxies

#> [[1]]

#> [[1]]$index

#> [1] 100

#>

#> [[1]]$proxy_index

#> [1] 98 99

#>

#> [[1]]$Rproxy

#> 100 98 99

#> 100 1.0000000 0.9568668 0.9745924

#> 98 0.9568668 1.0000000 0.9798682

#> 99 0.9745924 0.9798682 1.0000000

#>

#>

#> [[2]]

#> [[2]]$index

#> [1] 400

#>

#> [[2]]$proxy_index

#> [1] 395 396 397 398 399 401 402

#>

#> [[2]]$Rproxy

#> 400 395 396 397 398 399 401

#> 400 1.0000000 0.9495092 0.9661446 0.9793188 0.9730871 0.9306611 0.9105497

#> 395 0.9495092 1.0000000 0.9812294 0.9675572 0.9742288 0.9302869 0.8876271

#> 396 0.9661446 0.9812294 1.0000000 0.9841205 0.9905250 0.9454487 0.9054550

#> 397 0.9793188 0.9675572 0.9841205 1.0000000 0.9810106 0.9367627 0.9175545

#> 398 0.9730871 0.9742288 0.9905250 0.9810106 1.0000000 0.9522425 0.9119614

#> 399 0.9306611 0.9302869 0.9454487 0.9367627 0.9522425 1.0000000 0.8731959

#> 401 0.9105497 0.8876271 0.9054550 0.9175545 0.9119614 0.8731959 1.0000000

#> 402 0.8080771 0.7821419 0.7934351 0.8097815 0.7991366 0.7643812 0.7522628

#> 402

#> 400 0.8080771

#> 395 0.7821419

#> 396 0.7934351

#> 397 0.8097815

#> 398 0.7991366

#> 399 0.7643812

#> 401 0.7522628

#> 402 1.0000000

#>

#>

#> [[3]]

#> [[3]]$index

#> [1] 600

#>

#> [[3]]$proxy_index

#> [1] 601 606

#>

#> [[3]]$Rproxy

#> 600 601 606

#> 600 1.0000000 -0.8044757 0.8670863

#> 601 -0.8044757 1.0000000 -0.7193148

#> 606 0.8670863 -0.7193148 1.0000000Finally, the sim_extract_ld function will extract the LD

matrix for a set of variants.

ld_mat1 <- sim_extract_ld(sim_dat1_LD, index = 600:606, R_LD = ld_mat_list)

ld_mat1

#> 600 601 602 603 604 605

#> 600 1.0000000 -0.8044757 -0.6715969 -0.7920287 -0.7323562 -0.4605856

#> 601 -0.8044757 1.0000000 0.8354364 0.9791149 0.9404418 0.6067155

#> 602 -0.6715969 0.8354364 1.0000000 0.8138201 0.7891286 0.6555054

#> 603 -0.7920287 0.9791149 0.8138201 1.0000000 0.9363088 0.5849580

#> 604 -0.7323562 0.9404418 0.7891286 0.9363088 1.0000000 0.5890082

#> 605 -0.4605856 0.6067155 0.6555054 0.5849580 0.5890082 1.0000000

#> 606 0.8670863 -0.7193148 -0.5968298 -0.7200977 -0.7469780 -0.3902207

#> 606

#> 600 0.8670863

#> 601 -0.7193148

#> 602 -0.5968298

#> 603 -0.7200977

#> 604 -0.7469780

#> 605 -0.3902207

#> 606 1.0000000Specifying Sample Size, Sample Overlap, and Environmental Correlation

If two GWAS are performed on different traits using overlapping samples, the sampling errors of effect estimates will be correlated. If the two GWAS have sample sizes \(N_1\) and \(N_2\) with \(N_c\) overlapping samples, then the correlation of \(\hat{z}_{1j}\) and \(\hat{z}_{2j}\), \(z\)-scores for variant \(j\) in study 1 and study 2, is approximately \(\frac{N_c}{\sqrt{N_1 N_2}} \rho_{1,2}\) where \(\rho_{1,2}\) is the observational trait correlation (assuming the studies are conducted in the same super population). Below we describe how to specify the observational correlation and sample overlap.

Specifying Sample Size and Sample Overlap

The sample size argument, N, can be specified as a

scalar, a vector, a matrix, or a data frame. Both the scalar and matrix

specification indicate no overlapping samples between GWAS. To specify

sample overlap, we need to use the matrix or data frame formats. If

N is a matrix, it should have dimension \(M\times M\) with N[i,i] giving

the sample size of study \(i\) and

N[i,j] giving the number of samples that are in both study

\(i\) and study \(j\). In data frame format, \(N\) should have columns named

trait_1, … trait_[M] and N. The

trait_[x] columns will be interpreted as logicals and the

N column should give the number of samples in each

combination of studies. For example, the following specifications for

two traits are equivalent.

N <- matrix(c(60000, 30000, 30000, 60000), nrow = 2, ncol = 2)

N

#> [,1] [,2]

#> [1,] 60000 30000

#> [2,] 30000 60000

Ndf <- data.frame(trait_1 = c(1, 1, 0),

trait_2 = c(0, 1, 1),

N = rep(30000, 3))

Ndf

#> trait_1 trait_2 N

#> 1 1 0 30000

#> 2 1 1 30000

#> 3 0 1 30000When there are more than two traits, the data frame format contains

more information than the matrix format. This format is required by the

resample_inddata function (covered in a different

vignette). For sim_mv, either format is sufficient.

Using Sample Size 0 to Omit Traits

In some circumstances, we may want to generate true effects for a

trait but not generate summary statistics. In this case, we can use a

sample size of 0. Setting N = 0 will mean that

beta_hat, s_estimate, se_beta_hat

will be NA for all traits. Alternatively, if N

is a vector with some 0 elements, only those traits will be missing.

Finally, if N is a matrix, we can set the row and column

corresponding to the omitted trait to zero. For example, in the

specification below, we omit summary statistics for \(Z\), the third trait. We also specify some

overlapping samples in studies for the other three traits.

N <- matrix(c(50000, 10000, 0, 0,

10000, 40000, 0, 10000,

0, 0, 0, 0,

0, 10000, 0, 20000), nrow = 4)

N

#> [,1] [,2] [,3] [,4]

#> [1,] 50000 10000 0 0

#> [2,] 10000 40000 0 10000

#> [3,] 0 0 0 0

#> [4,] 0 10000 0 20000

sim_dat2 <- sim_mv(G = G,

N = N,

J = 100000,

h2 = c(0.3, 0.3, 0.5, 0.4),

pi = 0.01,

est_s = TRUE)

#> SNP effects provided for 100000 SNPs and 4 traits.

head(sim_dat2$beta_hat)

#> [,1] [,2] [,3] [,4]

#> [1,] 1.258828e-03 -0.002383374 NA 1.074629e-02

#> [2,] -8.580051e-03 -0.015482893 NA -7.281355e-03

#> [3,] -2.515356e-03 -0.001070368 NA -2.189328e-02

#> [4,] 5.422213e-05 -0.003164621 NA 8.103383e-03

#> [5,] -8.150978e-03 -0.005807492 NA 5.922625e-05

#> [6,] -5.861632e-03 -0.003012872 NA 3.302201e-03

head(sim_dat2$se_beta_hat)

#> [,1] [,2] [,3] [,4]

#> [1,] 0.004472136 0.005 NA 0.007071068

#> [2,] 0.004472136 0.005 NA 0.007071068

#> [3,] 0.004472136 0.005 NA 0.007071068

#> [4,] 0.004472136 0.005 NA 0.007071068

#> [5,] 0.004472136 0.005 NA 0.007071068

#> [6,] 0.004472136 0.005 NA 0.007071068

head(sim_dat2$s_estimate)

#> [,1] [,2] [,3] [,4]

#> [1,] 0.004453566 0.004976698 NA 0.007050114

#> [2,] 0.004471810 0.005008104 NA 0.007081267

#> [3,] 0.004471716 0.004976063 NA 0.007033821

#> [4,] 0.004459041 0.004982154 NA 0.007068942

#> [5,] 0.004480086 0.004961544 NA 0.007006829

#> [6,] 0.004472674 0.004987358 NA 0.007045390Understanding Genetic and Environmental Covariance

In the model used by GWASBrewer, each trait has a direct

genetic component, a direct environmental component, and components from

effects of other traits in the DAG. For example, in the four trait DAG

we have been working with, the underlying model really looks like

this:

In this picture, \(G_x\), \(G_y\), \(G_z\), and \(G_w\) are direct genetic components of each trait and \(E_x\), \(E_y\), \(E_z\), and \(E_w\) are direct environmental components. We always assume that the direct genetic components are independent of each other and of the environmental components. By default, we also assume that the environmental components are independent of each other (so all blue circles in the picture above are mutually independent). This means that, by default, the observational trait correlation is explained completely by the specified DAG. In this case, the default trait correlation is

sim_dat1$trait_corr

#> X Y Z W

#> X 1.0000000 0.4959207 0.4467774 0.2967570

#> Y 0.4959207 1.0000000 0.2220017 0.3840097

#> Z 0.4467774 0.2220017 1.0000000 -0.3025824

#> W 0.2967570 0.3840097 -0.3025824 1.0000000The simulation data object contains four matrices that describe trait

covarince, Sigma_E, the total environmental trait

covariance, Sigma_G the total genetic trait covariance,

trait_corr, the trait correlation equal to

Sigma_G + Sigma_E, and R, the row correlation

of beta_hat. R is equal to

trait_corr scaled by the a matrix of sample overlap

proportions.

Sigma_G is always determined by the DAG and the

heritabilities. Currently, there are two ways to modify

Sigma_E. The first is to specify R_obs which

directly specifies the observational trait correlation

(trait_corr). In some cases, it is possible to request an

observational correlation matrix that is impossible. For example, in our

example, \(Z\) has a strong negative

effect on \(W\) so it is not possible

that all four traits are mutually strongly positively correlated. We can

get an error using

R_obs <- matrix(0.8, nrow = 4, ncol = 4)

diag(R_obs) <- 1

wont_run <- sim_mv(G = G,

J = 50000,

N = 60000,

h2 = c(0.3, 0.3, 0.5, 0.4),

pi = 1000/50000,

R_obs = R_obs )

#> Error in value[[3L]](cond): R_obs is incompatible with trait relationships and heritability.A quick way to find out if your desired observational correlation is

feasible is to compute R_obs - Sigma_G and check that this

matrix is positive definite (i.e. check that it has all positive

eigenvalues).

An alternative way to specify the environmental correlation is to

specify R_E which gives the total correlation of

environmental components, i.e. cov2cor(Sigma_E).

Importantly, R_E is the correlation of the

total environmental components, not the direct

environmental components shown in the graph above. Any positive definite

correlation matrix is a valid input for R_E, so we could

use

R_E <- matrix(0.8, nrow = 4, ncol = 4)

diag(R_E) <- 1

sim_dat3 <- sim_mv(G = G,

J = 50000,

N = 60000,

h2 = c(0.3, 0.3, 0.5, 0.4),

pi = 1000/50000,

R_E = R_E)

#> SNP effects provided for 50000 SNPs and 4 traits.which results in a total trait correlation of

sim_dat3$trait_corr

#> X Y Z W

#> X 1.0000000 0.7109713 0.7020261 0.5677883

#> Y 0.7109713 1.0000000 0.5966303 0.6110510

#> Z 0.7020261 0.5966303 1.0000000 0.3158510

#> W 0.5677883 0.6110510 0.3158510 1.0000000It is not currently possible to specify the correlation of the direct environmental components.

Note that the environmental covariance and observational trait

correlation only influence the distribution of summary statistics if

there is overlap between GWAS samples. This means that

sim_dat3 in the previous code block is actually a sample

from exactly the same distribution as sim_dat1, because our

specification has no sample overlap. We can tell that this is the case

because sim_dat4$R is the identity, indicating that all

summary statistics are independent across traits.

sim_dat3$R

#> [,1] [,2] [,3] [,4]

#> [1,] 1 0 0 0

#> [2,] 0 1 0 0

#> [3,] 0 0 1 0

#> [4,] 0 0 0 1By contrast, in sim_dat2, we did have sample overlap, so

there is non-zero correlation between the summary statistics.

sim_dat2$R

#> [,1] [,2] [,3] [,4]

#> [1,] 1.0000000 0.1120147 0 0.0000000

#> [2,] 0.1120147 1.0000000 0 0.1355998

#> [3,] 0.0000000 0.0000000 0 0.0000000

#> [4,] 0.0000000 0.1355998 0 1.0000000