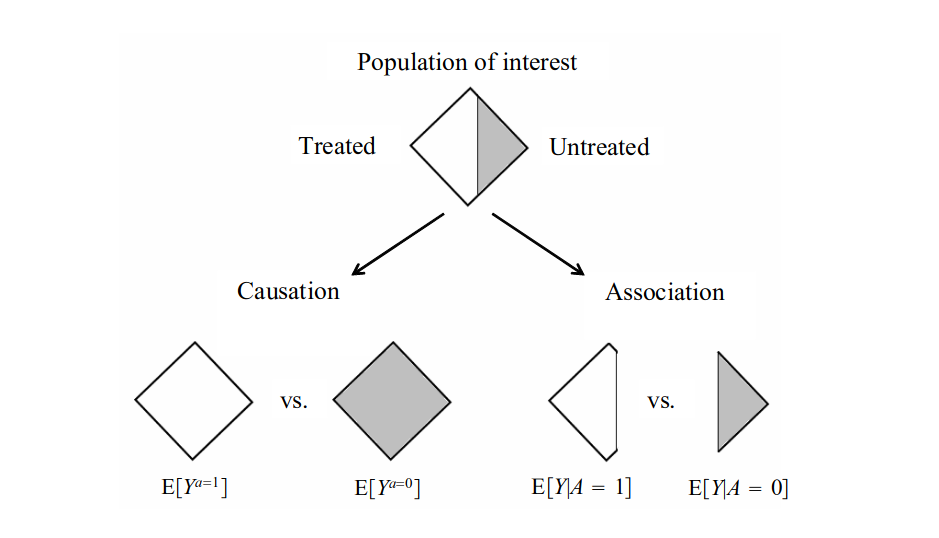

class: center, middle, inverse, title-slide .title[ # L1: Getting Started ] .author[ ### Jean Morrison ] .institute[ ### University of Michigan ] .date[ ### Lecture on 2025-01-08 (updated: 2025-01-08) ] --- `\(\newcommand{\ci}{\perp\!\!\!\perp}\)` ## Lecture Outline 1. Motivation and Introduction: What is Causal Inference? 1. Counterfactuals and Definitions of Causal Effects 1. Identifying a Causal Effect --- # 1. Introduction --- ## Motivation + The idea that causality is interesting is easy to motivate: The question "Why?" motivates nearly all scientific endeavors. + Causal inference formalizes what it means to answer this "Why?" question. + The idea that we need this formalization is much newer than the idea that causal questions are interesting. --- ## What is Causal Inference Causal inference consists of three elements: - A formal language and model of causality. (Philosophy/Logic) - A connection between this language and mathematical models. (Translation) - Statistical inference techniques for estimating causal parameters. (Statistics) --- ## Example: Smoking and Lung Cancer + In 1900 lung cancer was extremely rare. -- + By the 1920's incidence of lung cancer had increased dramatically. -- + Smoking was a hypothesized cause of lung cancer as early as 1912... -- + But so were: - Air pollution - Asphalt dust from new roads - Poison gas from WWI - Influenza pandemic of 1918 - Increasing use of radiography - Increasing clinical awareness of lung cancer - Aging population --- ## The Case Against Smoking -- - Observational studies showed a strong association between smoking and lung cancer. + Earliest studies used a case/control design. + Followed by prospective studies matching healthy smokers and non-smokers by age, sex, and occupation and following them over time. + All studies observed a large and robust association between smoking and lung cancer (Doll and Hill estimate an OR of 40 in 1954). -- - Supporting evidence comes from animal studies in the 1930's and 1940's: Exposing animals to tobacco products causes cancer. -- - Even more evidence from chemical analysis in the 1940's and 1950's: Cigarette smoke contains known cancer causing chemicals. + Much of this work is done by tobacco companies themselves. -- - By the 1950's tobacco companies also believe that tobacco use causes cancer. This information is kept secret. --- ## Challenges to the Smoking-Lung Cancer Link - Tobacco companies invested large amounts of money into research and advertising challenging the link between smoking and lung cancer. - In the 1960's only one third of doctors believed smoking to be a major cause of lung cancer. - RA Fisher was a famous challenger of the smoking `\(\rightarrow\)` lung cancer hypothesis: + Fisher pointed to a genetic factor linked to both smoking and lung cancer, arguing this factor may be a common cause of both. --- ## Fisher's Argument <div class="grViz html-widget html-fill-item" id="htmlwidget-017e36235cd5f1928a76" style="width:90%;height:180px;"></div> <script type="application/json" data-for="htmlwidget-017e36235cd5f1928a76">{"x":{"diagram":"digraph {\n\ngraph [layout = \"neato\",\n outputorder = \"edgesfirst\",\n bgcolor = \"white\"]\n\nnode [fontname = \"Helvetica\",\n fontsize = \"10\",\n shape = \"circle\",\n fixedsize = \"true\",\n width = \"0.5\",\n style = \"filled\",\n fillcolor = \"aliceblue\",\n color = \"gray70\",\n fontcolor = \"gray50\"]\n\nedge [fontname = \"Helvetica\",\n fontsize = \"8\",\n len = \"1.5\",\n color = \"gray80\",\n arrowsize = \"0.5\"]\n\n \"1\" [label = \"Smoking\", fontname = \"Helvetica\", shape = \"oval\", fontsize = \"10\", width = \"1\", fillcolor = \"#FFFFFF\", fontcolor = \"black\", color = \"black\", pos = \"0,0!\"] \n \"2\" [label = \"Genertic Variant\", fontname = \"Helvetica\", shape = \"oval\", fontsize = \"10\", width = \"1\", fillcolor = \"#FFFFFF\", fontcolor = \"black\", color = \"black\", pos = \"1.5,1!\"] \n \"3\" [label = \"Lung Cancer\", fontname = \"Helvetica\", shape = \"oval\", fontsize = \"10\", width = \"1\", fillcolor = \"#FFFFFF\", fontcolor = \"black\", color = \"black\", pos = \"3,0!\"] \n\"2\"->\"1\" [color = \"black\"] \n\"2\"->\"3\" [color = \"black\"] \n}","config":{"engine":"dot","options":null}},"evals":[],"jsHooks":[]}</script> --- ## What is Wrong with Fisher's Argument? - Fisher is right that an observational association between smoking and lung cancer could be explained by a common cause and not by a causal effect of smoking on lung cancer. - [Cornfield et al. (1959)](https://academic.oup.com/ije/article/38/5/1175/666926?login=true) pointed out that the effect size of the hypothetical genetic factor would have to be huge to explain the observed data. + It would have to be at least 9 times more prevalent in smokers than non-smokers and 60 times more prevalent in two-pack-a-day smokers. - The genetic hypothesis is also inconsistent with earlier low rates of lung cancer, animal studies, and reduced cancer rates in quitters. - Even though the common cause argument is impossible to disprove, the argument for causation is supported by multiple different lines of evidence and concrete mechanistic hypotheses. <!-- --- --> <!-- # Why did Fisher (and others) Get it Wrong? --> <!-- - Some have suggested that Fisher had conflicts of interest -- he had done work as a tobacco industry consultant and was himself a smoker. --> <!-- - Fisher's statement that the association between smoking and lung cancer could be explained by a common cause is correct. --> <!-- - But that model is inconsistent with many other lines of evidence. --> --- ## Lessons Part 1: Causality is Not Statistical - Causal inference cannot be achieved through only statistical procedures. It requires a model, assumptions, and information external to the study. -- - All causal analyses of observational data require un-provable assumptions. -- "[B]ehind every causal claim there must lie some causal assumption that is not discernible from the joint distribution and, hence, not testable in observational studies. Such assumptions are usually provided by humans, resting on expert judgement. Thus, the way humans organize and communicate experiential knowledge becomes an integral part of the study, for it determines the veracity of the judgements experts are requested to articulate." - Judea Pearl, [Causality 2nd Edition (2009)](http://bayes.cs.ucla.edu/BOOK-2K/) --- ## Lessons Part 2: Importance of Observational Data - The effect of smoking on lung cancer in humans was established entirely through observational studies. + Observational studies were supported by interventional experiments done in animals. - A randomized trial of a treatment believed to be harmful is unethical. - Furthermore, even if it was ethical, it is impractical to expect study participants to adhere to a decades-long behavioral assignment. - Many important factors determining human quality of life can only be studied observationally. --- ## Early Foundations of Causal Theory - Neyman 1923: Notation and formalization of potential outcomes introduced. - Fisher 1925: Physical randomization of units as the "reasoned basis" for inference. - Wright 1921: Introduced graphical models and path analysis. --- ## Languages of Causality -- + Potential Outcomes/counterfactuals: - Proposes the existence of unobserved outcomes for each unit under different possible exposures or treatments. - First formalized by Neyman (1923), further developed by Donald Rubin (1974 and onward) and others. - "Rubin causal model". -- + Graphs: - Represents causal relationships between observed and unobserved variables as directed edges in a graph. - Causal interventions are represented as modifications of the graph. - Introduced by Wright (1921), further developed by Judea Pearl (1988 and onward) and others. -- + Structural Equations: - Represents causal relationships as a series of equations describing conditional probability distributions. - Also introduced by Wright in 1921. - More work by Pearl, Haavelmo, Duncan, and many more. -- + Under some conditions, all three languages are equivalent/mutually compatible. --- # 2. Counterfactuals and Treatment Effects <!-- # Languages of Causality --> <!-- + Causality described using potential outcomes: --> <!-- - Neyman, 1923 (statistics) --> <!-- - Lewis, 1973 (philosophy) --> <!-- - Rubin 1974 (statistics) --> <!-- - Robins, 1986 (epidemiology) --> <!-- + Causality described using graphs: --> <!-- + Wright, 1921 (genetics) --> <!-- + Pearl, 1988 (CS, statistics) --> <!-- + Sprites, Glymour, Scheines, 1993 (philosophy) --> <!-- + Causality described using structural equations: --> <!-- - Wright, 1921 (genetics) --> <!-- - Haavelmo, 1943 (econometrics) --> <!-- - Duncan, 1975 (social sciences) --> <!-- - Pearl, 2000 (CS, statistics) --> <!-- --- --> --- ## Counterfactuals/Potential Outcomes + What does it mean to say that `\(A\)` causes `\(Y\)`? -- + A counterfactual value, `\(Y_i(A_i = a)\)` is the value of `\(Y\)` the `\(i\)`th individual **would have had** if `\(A\)` had been **intervened on** and set to `\(a\)`. -- + Many equivalent notations: - `\(Y(A = a)\)`, `\(Y(a)\)`: I will primarily use these notations. - `\(Y^a\)`: This is the main notation in Hernán and Robins. - `\(Y\vert \ do(A = a)\)`: This notation emphasizes the intervention of setting `\(A\)` equal to `\(a\)` and is favored by Judea Pearl. There are some subtle differences between the "do operator" and counterfactuals. -- + A counterfactual fundamentally supposes a hypothetical intervention (treatment). <!-- + I will (try to) stick with `\(Y(A = a)\)` or `\(Y(a)\)` when the meaning is unambiguous. --> <!-- -- --> <!-- + We can only observe `\(Y_i\)` under a single value of `\(A_i\)`, so `\(Y_i(A_i = a)\)` is missing for all but one value of `\(a\)`. --> --- ## Example: New Surgical Procedure - Patients with a particular condition require surgery. - An alternative new surgical procedure is proposed. - We are interested in whether the new procedure leads to better outcomes than the standard procedure. - Let `\(A_i = 0\)` indicate that patient `\(i\)` received the original standard of care procedure and `\(A_i = 1\)` indicate that they recieved the new procedure. - Let `\(Y_i = 0\)` indicate that the patient survived for at least 30 days after the procedure and `\(Y_i = 1\)` indicate that they died within 30 days of the procedure. --- ## Example: New Surgical Procedure Below is a full counterfactual table for 8 patients. <table> <thead> <tr> <th style="text-align:right;"> </th> <th style="text-align:right;"> \(Y(A=0)\) </th> <th style="text-align:right;"> \(Y(A=1)\) </th> </tr> </thead> <tbody> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 1 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 1 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 1 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 2 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 1 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 0 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 3 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 0 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 4 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 0 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 5 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 1 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 6 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 1 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 1 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 7 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 1 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 8 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 1 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 0 </td> </tr> </tbody> </table> In real data, we only observe one of the two entries for each person. --- ## Sharp vs Average Causal Null + Sharp causal null: No effect of treatment for any individual, `$$Y_i(A_i = 1) = Y_i(A_i = 0) \qquad \forall i$$` + Average causal null: The average causal effect is zero, `$$E[Y(A = 0)] = E[Y(A = 1)]$$` + We are usually interested in the average causal null. --- ## Sharp vs Average Causal Null In our example, the sharp null is false, but the average null is true. <table> <thead> <tr> <th style="text-align:right;"> </th> <th style="text-align:right;"> \(Y(A=0)\) </th> <th style="text-align:right;"> \(Y(A=1)\) </th> </tr> </thead> <tbody> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 1 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 1 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 1 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 2 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 1 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 0 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 3 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 0 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 4 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 0 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 5 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 1 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 6 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 1 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 1 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 7 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 1 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 8 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 1 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 0 </td> </tr> </tbody> </table> --- ## Measures of Treatment Effects + Average treatment effect (ATE): `\(E[Y(1)] - E[Y(0)] = E[Y_i(A1) - Y_i(0)]\)` + Risk ratio (RR): `\(E[Y(1)]/E[Y(0)]\)` + Odds ratio (OR; for binary outcomes): `\(\frac{E[Y(1)]/(1-E[Y(1)])}{E[Y(0)]/(1-E[Y(0)]}\)` + Null hypotheses ATE `\(=0\)`, RR `\(=1\)`, and OR `\(=1\)` are equivalent. + The ATE can be interpreted either as the difference in average outcome between groups or as the average difference. + This is not true for RR and OR. RR is not equal to the average risk ratio over the population. --- ## Counterfactuals and Missing Data + The counterfactual framework turns causal inference into a missing data problem. + Even if we were able to observe `\(A\)` and `\(Y\)` for the entire population, uncertainty would remain in our estimate of the ATE because we cannot observe both `\(Y_i(1)\)` and `\(Y_i(0)\)` for the same individual. + This has been called the "fundamental problem of causal inference." --- ## Sample vs Population Treatment Effect + We very rarely sample the entire population of interest. + Sample average treatment effect (SATE): `\(\frac{1}{n}\sum_{i = 1}^{n} Y_i(1) - \frac{1}{n}\sum_{i = 1}^{n} Y_i(0)\)` + Population average treatment effect (PATE): `\(E[Y(1)] - E[Y(0)]\)`, with expectation taken over a super-population. + We are almost always interested in the PATE. Most of the time, when we say ATE we mean PATE. + Identifying the population is a scientific (rather than a statistical) task. --- <!-- ## Non-Deterministic Counterfactuals --> <!-- + So far we have seen two sources of uncertainty in the ATE: --> <!-- - Missing counterfactual outcomes --> <!-- - Sampling variation --> <!-- + A third source is randomness in the counterfactual outcome. --> <!-- + Rather than thinking of `\(Y_i(A_i = a)\)` as a deterministic value, we can think of it as a random variable with individual specific (random) cdf `\(F_{Y_i(a)}(y)\)`. --> <!-- + We will abbreviate `\(F_{Y_i(a)}(y)\)` to `\(F_{a,i}\)`. --> <!-- --- --> <!-- ## Non-Deterministic Counterfactuals --> <!-- + If `\(Y_i(A_i = a)\)` is a random variable, the ATE is a double expectation: --> <!-- `$$E[Y(A = a)] = E\left \lbrace E[ Y_i(A_i = a) \vert F_{a,i} ] \right \rbrace$$` --> <!-- with the inside expectation taken over the distribution of `\(Y_i(A_i = a)\)` and the outer expectation taken over the population. --> <!-- + Let `\(F_{a} = E[F_{a,i}]\)` be the average counterfactual cdf. --> <!-- `$$E[Y(A =a)] = E\left[\int y \ dF_{a,i}(y) \right] = \int y \ dE[F_{a,i}(y)] = \int y \ dF_a(y)$$` --> <!-- + So, the average counterfactual value is the expectation w.r.t the average counterfactual cdf. --> <!-- + The distinction between deterministic and non-deterministic counterfactuals doesn't matter for average effects. --> <!-- --- --> ## Causation vs Association  Fig 1.1 from HR --- ## Surgery Example Continued What is the average causal effect, `\(E[Y(1)] - E[Y(0)]\)`? What is the association `\(E[Y \vert A = 1] - E[Y \vert A = 0]\)`? <table class="table" style="font-size: 14px; width: auto !important; float: left; margin-right: 10px;"> <thead> <tr> <th style="text-align:right;"> </th> <th style="text-align:right;"> \(Y(A=0)\) </th> <th style="text-align:right;"> \(Y(A=1)\) </th> <th style="text-align:right;"> \(A\) </th> </tr> </thead> <tbody> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 1 </td> <td style="text-align:right;font-weight: bold;color: black !important;"> 1 </td> <td style="text-align:right;color: grey !important;"> 1 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 0 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 2 </td> <td style="text-align:right;font-weight: bold;color: black !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;color: grey !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 0 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 3 </td> <td style="text-align:right;font-weight: bold;color: black !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;color: grey !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 0 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 4 </td> <td style="text-align:right;font-weight: bold;color: black !important;"> 1 </td> <td style="text-align:right;color: grey !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 0 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 5 </td> <td style="text-align:right;font-weight: bold;color: black !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;color: grey !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 0 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 6 </td> <td style="text-align:right;font-weight: bold;color: black !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;color: grey !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 0 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 7 </td> <td style="text-align:right;font-weight: bold;color: black !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;color: grey !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 0 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 8 </td> <td style="text-align:right;font-weight: bold;color: black !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;color: grey !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 0 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 9 </td> <td style="text-align:right;font-weight: bold;color: black !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;color: grey !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 0 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 10 </td> <td style="text-align:right;font-weight: bold;color: black !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;color: grey !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 0 </td> </tr> </tbody> </table> <table class="table" style="font-size: 14px; width: auto !important; margin-right: 0; margin-left: auto"> <thead> <tr> <th style="text-align:right;"> </th> <th style="text-align:right;"> \(Y(A=0)\) </th> <th style="text-align:right;"> \(Y(A=1)\) </th> <th style="text-align:right;"> \(A\) </th> </tr> </thead> <tbody> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 11 </td> <td style="text-align:right;color: grey !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;font-weight: bold;color: black !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 1 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 12 </td> <td style="text-align:right;color: grey !important;"> 1 </td> <td style="text-align:right;font-weight: bold;color: black !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 1 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 13 </td> <td style="text-align:right;color: grey !important;"> 1 </td> <td style="text-align:right;font-weight: bold;color: black !important;"> 1 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 1 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 14 </td> <td style="text-align:right;color: grey !important;"> 1 </td> <td style="text-align:right;font-weight: bold;color: black !important;"> 1 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 1 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 15 </td> <td style="text-align:right;color: grey !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;font-weight: bold;color: black !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 1 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 16 </td> <td style="text-align:right;color: grey !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;font-weight: bold;color: black !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 1 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 17 </td> <td style="text-align:right;color: grey !important;"> 1 </td> <td style="text-align:right;font-weight: bold;color: black !important;"> 1 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 1 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 18 </td> <td style="text-align:right;color: grey !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;font-weight: bold;color: black !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 1 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 19 </td> <td style="text-align:right;color: grey !important;"> 1 </td> <td style="text-align:right;font-weight: bold;color: black !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 1 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 20 </td> <td style="text-align:right;color: grey !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;font-weight: bold;color: black !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 1 </td> </tr> </tbody> </table> .small[**Bold** = Observed] --- ## Surgery Example Continued Average causal effect: `\(0.2 - 0.35 = -0.15\)` Association: `\(0.3 - 0.2 = 0.1\)` <table class="table" style="font-size: 14px; width: auto !important; float: left; margin-right: 10px;"> <thead> <tr> <th style="text-align:right;"> </th> <th style="text-align:right;"> \(Y(A=0)\) </th> <th style="text-align:right;"> \(Y(A=1)\) </th> <th style="text-align:right;"> \(A\) </th> </tr> </thead> <tbody> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 1 </td> <td style="text-align:right;font-weight: bold;color: black !important;"> 1 </td> <td style="text-align:right;color: grey !important;"> 1 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 0 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 2 </td> <td style="text-align:right;font-weight: bold;color: black !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;color: grey !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 0 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 3 </td> <td style="text-align:right;font-weight: bold;color: black !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;color: grey !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 0 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 4 </td> <td style="text-align:right;font-weight: bold;color: black !important;"> 1 </td> <td style="text-align:right;color: grey !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 0 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 5 </td> <td style="text-align:right;font-weight: bold;color: black !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;color: grey !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 0 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 6 </td> <td style="text-align:right;font-weight: bold;color: black !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;color: grey !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 0 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 7 </td> <td style="text-align:right;font-weight: bold;color: black !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;color: grey !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 0 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 8 </td> <td style="text-align:right;font-weight: bold;color: black !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;color: grey !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 0 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 9 </td> <td style="text-align:right;font-weight: bold;color: black !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;color: grey !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 0 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 10 </td> <td style="text-align:right;font-weight: bold;color: black !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;color: grey !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 0 </td> </tr> </tbody> </table> <table class="table" style="font-size: 14px; width: auto !important; margin-right: 0; margin-left: auto"> <thead> <tr> <th style="text-align:right;"> </th> <th style="text-align:right;"> \(Y(A=0)\) </th> <th style="text-align:right;"> \(Y(A=1)\) </th> <th style="text-align:right;"> \(A\) </th> </tr> </thead> <tbody> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 11 </td> <td style="text-align:right;color: grey !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;font-weight: bold;color: black !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 1 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 12 </td> <td style="text-align:right;color: grey !important;"> 1 </td> <td style="text-align:right;font-weight: bold;color: black !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 1 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 13 </td> <td style="text-align:right;color: grey !important;"> 1 </td> <td style="text-align:right;font-weight: bold;color: black !important;"> 1 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 1 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 14 </td> <td style="text-align:right;color: grey !important;"> 1 </td> <td style="text-align:right;font-weight: bold;color: black !important;"> 1 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 1 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 15 </td> <td style="text-align:right;color: grey !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;font-weight: bold;color: black !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 1 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 16 </td> <td style="text-align:right;color: grey !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;font-weight: bold;color: black !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 1 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 17 </td> <td style="text-align:right;color: grey !important;"> 1 </td> <td style="text-align:right;font-weight: bold;color: black !important;"> 1 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 1 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 18 </td> <td style="text-align:right;color: grey !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;font-weight: bold;color: black !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 1 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 19 </td> <td style="text-align:right;color: grey !important;"> 1 </td> <td style="text-align:right;font-weight: bold;color: black !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 1 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 20 </td> <td style="text-align:right;color: grey !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;font-weight: bold;color: black !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 1 </td> </tr> </tbody> </table> .small[**Bold** = Observed] --- # 3. Identifying a Causal Effect --- ## Identification - A parameter is identifiable if it is theoretically estimable with a large enough sample. - Formally, let `\(\mathcal{P} = \lbrace P_\theta \vert \theta \in \Theta \rbrace\)` be a set of distributions parameterized by `\(\theta\)`. Then `\(\theta\)` is identifiable if unique values of `\(\theta\)` correspond to unique distributions, i.e. `\(P_{\theta} \neq P_{\theta^\prime}\)` if `\(\theta \neq \theta^\prime\)`. - Identifiability is a property of the model, not of a particular estimation procedure or a data set. - Knowing that `\(\theta\)` is theoretically identifiable doesn't mean we can estimate it well in our data. - It also doesn't provide us with an estimation procedure. --- ## Identification Example: Co-linearity. Suppose we model observations of `\((Y, X_1, X_2)\)` as `$$Y_i = \beta_0 + \beta_1 X_{1,i} + \beta_2 X_{2,i} + \epsilon_i$$` and `\(X_{1,i} = X_{2,i}\)` for all `\(i\)`. Then `\((\beta_0, \beta_1, \beta_2)\)` is not identifiable because multiple values of `\(\beta_1\)` and `\(\beta_2\)` correspond to the same distribution of `\(Y\)`. --- ## Identifiability in Causal Inference - Usually in causal inference, we are interested in ideintifying a function of counterfactuals like `\(E[Y(a)]\)` or the ATE. --- ## Conditions for Identifying an Average Counterfactual + Suppose we only observe `\(A\)` and `\(Y\)`. When is it possible to estimate `\(E[Y(a)]\)`? -- + We must be able to estimate `\(E[Y(a)]\)` for all values of `\(a\)`, so we must have $$ E[Y(a)] = E[Y \vert A = a]$$ -- + This condition holds under three assumptions: - Consistency - Stable Unit Treatment Value Assumption (SUTVA) - Exchangeability (exogeneity) --- ## Consistency - The observed value of `\(Y_i\)` is the same as the counterfactual value `\(Y_i(A_i = a_i)\)`, where `\(a_i\)` is the treatment individual `\(i\)` actually received. `$$Y_i = Y_i(A_i = a_i)$$` - In other words, the act of intervening to set `\(A_i\)` to `\(a_i\)` has no effect on the counterfactual value `\(Y_i(a_i)\)`. -- Surgery example: + A person's chance of surviving after surgery is the same whether they chose their treatment type of their own accord or were assigned to the treatment they would have chosen anyway. -- + Whether or not consistency holds may depend on the nature of the hypothesized intervention. --- ## Stable Unit Treatment Value Assumption 1. There are no different versions of treatment available to an individual and the treatment level `\(a\)` is unambiguous for all values of `\(a\)`. -- 1. No interference: The counterfactual outcome for unit `\(i\)`, `\(Y_i (A_i = a)\)` is independent of the treatment received by other units in the study. -- + Formally, let `\(\mathbf{A} = (A_1, \dots, A_n)\)` be the vector of treatment assignments for all units, with `\(\mathbf{a}\)` being a single realization of `\(\mathbf{A}\)`. Let `\(a_i\)` be the `\(i\)`th element of `\(\mathbf{a}\)` and `\(\mathcal{A}^n\)` be the sample space of `\(\mathbf{A}\)`. Let `\(Y_i(\mathbf{A} = \mathbf{a})\)` be the counterfactual value of `\(Y_i\)` under the treatment vector `\(\mathbf{a}\)`. No interference is the condition that $$ Y_i(\mathbf{A}= \mathbf{a}) = Y_i(A_i = a_i) \ \ \ \forall\ \ \mathbf{a} \in \mathcal{A}^{n} $$ --- ## Stable Unit Treatment Value Assumption Pair discussion: + Can you think of a time that "no different versions of treatment" may not hold? + Can you think of a time "no interference" may not hold? --- ## Subtlty in No Different Versions of Treatment + The "no different versions" assumption says that each individual only has one version of a given treatment available to them. + However, treatment may look different for different units. + For example, suppose we want to compare treatments "get an annual checkup from your PCP" vs "do not get an annual checkup." + Each individual may have a different PCP who does different kinds of tests. + As long as they only have one PCP option, or the PCP is assigned to them, "no different versions" is satisfied. + "No different versions" would be violated if individuals could select their PCP based on meaningful information. --- ## Exchangeability + Exchangeability says that `\(Y(a)\)` is independent of the treatment actually received: `\(Y(a) \ci A\)`. -- + Question: How is `\(Y(a) \ci A\)` different from `\(Y \ci A\)`? -- + Mean exchangeability: `$$E[Y(a) \vert A = a^\prime] = E[Y(a) \vert A = a^{\prime \prime}] \qquad \forall a^\prime, a^{\prime \prime} \in \mathcal{A}.$$` -- + Mean exchangeability is sufficient to prove `\(E[Y(a)] = E[Y \vert A = a].\)` -- + For dichotomous `\(Y\)`, mean exchangeability and exchangeability are equivalent. -- + What about for non-dichotomous `\(Y\)`? <!-- -- --> <!-- + Full exchangeability: Let `\(Y^{\mathcal{A}} = \left \lbrace Y(a), Y(a^\prime), \dots \right \rbrace\)` be the set of all counterfactual outcomes ( `\(Y^{\mathcal{A}} = \left \lbrace Y(1), Y(0) \right \rbrace\)` for a dichotomous treatment). Full exchangeability states that --> <!-- $$ --> <!-- Y^{\mathcal{A}} \ci A --> <!-- $$ --> --- ## Exchangeability Example: Does exchangeability hold in these data? <table class="table" style="font-size: 14px; width: auto !important; float: left; margin-right: 10px;"> <thead> <tr> <th style="text-align:right;"> </th> <th style="text-align:right;"> \(Y(A=0)\) </th> <th style="text-align:right;"> \(Y(A=1)\) </th> <th style="text-align:right;"> \(A\) </th> </tr> </thead> <tbody> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 1 </td> <td style="text-align:right;font-weight: bold;color: black !important;"> 1 </td> <td style="text-align:right;color: grey !important;"> 1 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 0 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 2 </td> <td style="text-align:right;font-weight: bold;color: black !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;color: grey !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 0 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 3 </td> <td style="text-align:right;font-weight: bold;color: black !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;color: grey !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 0 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 4 </td> <td style="text-align:right;font-weight: bold;color: black !important;"> 1 </td> <td style="text-align:right;color: grey !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 0 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 5 </td> <td style="text-align:right;font-weight: bold;color: black !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;color: grey !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 0 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 6 </td> <td style="text-align:right;font-weight: bold;color: black !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;color: grey !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 0 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 7 </td> <td style="text-align:right;font-weight: bold;color: black !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;color: grey !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 0 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 8 </td> <td style="text-align:right;font-weight: bold;color: black !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;color: grey !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 0 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 9 </td> <td style="text-align:right;font-weight: bold;color: black !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;color: grey !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 0 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 10 </td> <td style="text-align:right;font-weight: bold;color: black !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;color: grey !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 0 </td> </tr> </tbody> </table> <table class="table" style="font-size: 14px; width: auto !important; margin-right: 0; margin-left: auto"> <thead> <tr> <th style="text-align:right;"> </th> <th style="text-align:right;"> \(Y(A=0)\) </th> <th style="text-align:right;"> \(Y(A=1)\) </th> <th style="text-align:right;"> \(A\) </th> </tr> </thead> <tbody> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 11 </td> <td style="text-align:right;color: grey !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;font-weight: bold;color: black !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 1 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 12 </td> <td style="text-align:right;color: grey !important;"> 1 </td> <td style="text-align:right;font-weight: bold;color: black !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 1 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 13 </td> <td style="text-align:right;color: grey !important;"> 1 </td> <td style="text-align:right;font-weight: bold;color: black !important;"> 1 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 1 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 14 </td> <td style="text-align:right;color: grey !important;"> 1 </td> <td style="text-align:right;font-weight: bold;color: black !important;"> 1 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 1 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 15 </td> <td style="text-align:right;color: grey !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;font-weight: bold;color: black !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 1 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 16 </td> <td style="text-align:right;color: grey !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;font-weight: bold;color: black !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 1 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 17 </td> <td style="text-align:right;color: grey !important;"> 1 </td> <td style="text-align:right;font-weight: bold;color: black !important;"> 1 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 1 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 18 </td> <td style="text-align:right;color: grey !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;font-weight: bold;color: black !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 1 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 19 </td> <td style="text-align:right;color: grey !important;"> 1 </td> <td style="text-align:right;font-weight: bold;color: black !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 1 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 20 </td> <td style="text-align:right;color: grey !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;font-weight: bold;color: black !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 1 </td> </tr> </tbody> </table> .small[**Bold** = Observed] <!-- `\(E[Y(A = 0) \vert A = 0] = 0.2\)`, `\(E[Y(A = 0) \vert A = 1] = 0.5\)` --> <!-- `\(E[Y(A = 1) \vert A = 0] = 0.1\)`, `\(E[Y(A = 1) \vert A = 1] = 0.3\)` --> --- ## Exchangeability Example: `\(E[Y(A = 0) \vert A = 0] = 0.2\)`, `\(E[Y(A = 0) \vert A = 1] = 0.5\)` `\(E[Y(A = 1) \vert A = 0] = 0.1\)`, `\(E[Y(A = 1) \vert A = 1] = 0.3\)` <table class="table" style="font-size: 14px; width: auto !important; float: left; margin-right: 10px;"> <thead> <tr> <th style="text-align:right;"> </th> <th style="text-align:right;"> \(Y(A=0)\) </th> <th style="text-align:right;"> \(Y(A=1)\) </th> <th style="text-align:right;"> \(A\) </th> </tr> </thead> <tbody> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 1 </td> <td style="text-align:right;font-weight: bold;color: black !important;"> 1 </td> <td style="text-align:right;color: grey !important;"> 1 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 0 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 2 </td> <td style="text-align:right;font-weight: bold;color: black !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;color: grey !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 0 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 3 </td> <td style="text-align:right;font-weight: bold;color: black !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;color: grey !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 0 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 4 </td> <td style="text-align:right;font-weight: bold;color: black !important;"> 1 </td> <td style="text-align:right;color: grey !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 0 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 5 </td> <td style="text-align:right;font-weight: bold;color: black !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;color: grey !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 0 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 6 </td> <td style="text-align:right;font-weight: bold;color: black !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;color: grey !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 0 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 7 </td> <td style="text-align:right;font-weight: bold;color: black !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;color: grey !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 0 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 8 </td> <td style="text-align:right;font-weight: bold;color: black !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;color: grey !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 0 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 9 </td> <td style="text-align:right;font-weight: bold;color: black !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;color: grey !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 0 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 10 </td> <td style="text-align:right;font-weight: bold;color: black !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;color: grey !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 0 </td> </tr> </tbody> </table> <table class="table" style="font-size: 14px; width: auto !important; margin-right: 0; margin-left: auto"> <thead> <tr> <th style="text-align:right;"> </th> <th style="text-align:right;"> \(Y(A=0)\) </th> <th style="text-align:right;"> \(Y(A=1)\) </th> <th style="text-align:right;"> \(A\) </th> </tr> </thead> <tbody> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 11 </td> <td style="text-align:right;color: grey !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;font-weight: bold;color: black !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 1 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 12 </td> <td style="text-align:right;color: grey !important;"> 1 </td> <td style="text-align:right;font-weight: bold;color: black !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 1 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 13 </td> <td style="text-align:right;color: grey !important;"> 1 </td> <td style="text-align:right;font-weight: bold;color: black !important;"> 1 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 1 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 14 </td> <td style="text-align:right;color: grey !important;"> 1 </td> <td style="text-align:right;font-weight: bold;color: black !important;"> 1 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 1 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 15 </td> <td style="text-align:right;color: grey !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;font-weight: bold;color: black !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 1 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 16 </td> <td style="text-align:right;color: grey !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;font-weight: bold;color: black !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 1 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 17 </td> <td style="text-align:right;color: grey !important;"> 1 </td> <td style="text-align:right;font-weight: bold;color: black !important;"> 1 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 1 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 18 </td> <td style="text-align:right;color: grey !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;font-weight: bold;color: black !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 1 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 19 </td> <td style="text-align:right;color: grey !important;"> 1 </td> <td style="text-align:right;font-weight: bold;color: black !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 1 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:right;"> 20 </td> <td style="text-align:right;color: grey !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;font-weight: bold;color: black !important;"> 0 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 1 </td> </tr> </tbody> </table> .small[**Bold** = Observed] --- ## Identification Theorem - Theorem: If consistency, SUTVA, and exchangeability hold, then `$$Y(a) \overset{d}{=} Y | A = a,$$` where `\(\overset{d}{=}\)` means equal in distribution. -- - This theorem implies that `\(E[Y(a)]\)` and any other function of population distribution of `\(Y(a)\)` is identifiable because we can observe `\(Y \vert A = a\)`. -- - Proof: `$$P[Y(a) \leq y] = P[Y(a) \leq y \vert A = a] \ \ \ \text{(exchangeability)}$$` `$$= P[Y \leq y \vert A = a] \ \ \ \text{(consistency)}$$` -- Corrolary: If consistency, SUTVA, and exchangeability hold then `\(E[Y(a)] = E[Y \vert A = a]\)` --- ## Where did SUTVA come in? + If the levels of `\(A\)` are not clearly defined, the causal question is ill-defined (i.e. `\(Y(a)\)` is poorly defined). + In the presence of interference, there is no single value of `\(Y_i(a_i)\)`. Instead, we must discuss `\(Y_i(\mathbf{a})\)`, the potential outcome given the entire vector of treatment assignments. --- ## Simple Randomized Experiments + Units are assigned a treatment value using a randomization procedure that is independent of all unit characteristics (e.g. flip a coin). + For now, we assume full compliance (everyone assigned treatment `\(a\)` receives treatment `\(a\)`). + Exchangeability holds by design. + So, we can estimate the ATE as long as consistency and SUTVA hold. + One estimator is just the difference in average outcomes: `$$\frac{1}{n_{1}}\sum_{i: A_i = 1}Y_i - \frac{1}{n_2}\sum_{i:A_i = 0}Y_i = \bar{Y}_1 - \bar{Y}_0$$` --- ## Conditionally Randomized Experiments + Units are assigned a treatment with probability depending on a set of features, `\(L\)`. + If `\(L\)` and `\(Y(a)\)` are not independent, then exchangeability does not (generally) hold. + However, we can still identify the ATE if we have access to the randomization features `\(L\)`. --- ## Example + We are conducting a trial for the new surgery option. + Let `\(L = 0\)` indicate that a patient is less sick and `\(L = 1\)` indicate that they are more sick. + We decide on a randomization scheme in which sicker patients are more likely to receive the new treatment. We set `\(P(A = 1 \vert L = 0) = 0.5\)` and `\(P(A = 1 \vert L = 1) = 0.75\)`. --- ## Example <center> <img src="img/1_trial1.png" width="80%" /> </center> --- ## Conditional Exchangeability + Notice that our trial looks like two fully randomized trials combined. - In one trial, the target population is patients with `\(L = 0\)` and the treatment probability is 0.5. - In the other, the target population is patients with `\(L = 1\)` and the treatment probability is 0.75. -- + Conditional exchangeability captures the idea that data are randomized *within* levels of `\(L\)`. -- + Conditional exchangeability holds with respect to a set of variables `\(L\)`, if `$$Y(a) \ci A\ \vert\ L$$` --- ## Stratum Specific Causal Effects and Standardization + Exchangeability holds within levels of `\(L\)`, so `\(E[Y(a) \vert L = l]\)` is identifiable. `$$E[Y(a) \vert L = l] = E[Y \vert A = a, L = l]$$` -- + If we want to estimate the population level marginal counterfactual value of `\(Y\)` under treatment `\(A = a\)`, we can simply weight our estimates by the population frequency of `\(L\)`: `$$E[Y(a)] = \sum_{l}E[Y(a) \vert L = l]P[L = l] \\= \sum_{l}E[Y \vert A = a, L = l]P[L = l]$$` -- + This is called the standardized mean (standardized by population frequencies of `\(L\)`). --- ## Example <center> <img src="img/1_trial1.png" width="80%" /> </center> `$$E[Y(0)] = \sum_{l = 0, 1}E[Y \vert A = 0, L = l]P[L = l] = (1/3)\cdot (6/10) + 1 \cdot (4/10) = 0.6\\ E[Y(1)] = \sum_{l = 0, 1}E[Y \vert A = 1, L = l]P[L = l] = 0 \cdot (6/10) + (2/3) \cdot (4/10) = 0.27\\$$` --- ## Positivity + The standardization trick doesn't work if, within one level of `\(L\)`, patients never (or always) receive treatment. -- + The positivity condition states that at all individuals have some chance of receiving any treatment: `$$P[A = a \vert L = l] > 0 \ \ \forall a, l$$` --- ## Identification Theorem (Conditional) Theorem: If consistency, SUTVA, conditional exchangeability, *and positivity* hold, then `$$Y(a) \vert\ L=l\ \overset{d}{=}\ Y |\ L = l, A = a.$$` -- We can use exactly the same proof as the non-conditional theorem, conditioning on `\(L\)` in each step. Proof: `$$P[Y(a) \leq y \vert L = l] = P[Y(a) \leq y \vert L=l, A = a] \ \ \ \text{(conditional exchangeability)}$$` `$$= P[Y \leq y \vert L=l, A = a] \ \ \ \text{(consistency)}$$` --- ## Inverse Probability Weighting + Rather than using the standardization method, we can think of our trial as a weighted sampling from a larger, fully randomized trial with `\(2N\)` participants. + To create this large *pseudo-population*, we imagine duplicating each member of our trial. One member of each pair receives treatment `\(A = 1\)` and the other receives treatment `\(A = 0\)`. + In the pseudo-population, `\(P[A = a \vert L = l] = 0.5\)` for every level of `\(l\)`, so `\(Y(a) \ci A\)`. + This means that, in the pseudo-population, `\(E[Y \vert A = a]\)` estimates the counterfactual mean `\(E[Y(a)]\)`. --- # Inverse Probability Weighting <img src="img/1_trial2.png" width="80%" /> --- ## Inverse Probability Weighting + We can imagine that each individual in our trial was sampled from the larger pseudo-population with probability conditional on `\(L\)` and `\(A\)`. - In our study we selected half of participants with `\(A_i = 0\)` and `\(L_i = 0\)` - Half of participants with `\(A_i = 1\)` and `\(L = 0\)` - One quarter of participants with `\(A_i = 0\)` and `\(L = 1\)` - Three quarters of participants with `\(A_i = 1\)` and `\(L = 1\)` --- # Inverse Probability Weighting <img src="img/1_trial3.png" width="80%" /> --- # Inverse Probability Weighting + We can recover the estimate from the pseudo-population by weighting each participant by the number of units in the larger study that they represent: - `\(A_i=0\)`, `\(L_i=0\)`: `\(1/0.5 = 2\)` - `\(A_i = 1\)`, `\(L_i = 0\)`: `\(1/0.5 = 2\)` - `\(A_i = 0\)`, `\(L_i = 1\)`: `\(1/0.25 = 4\)` - `\(A_i = 1\)`, `\(L_i = 0\)`: `\(1/0.75 = 1.33\)` --- ## Inverse Probability Weighting + Formally, let `\(f_{A \vert L}(a\vert l)\)` be the conditional pdf of `\(A\)` given `\(L\)`. + We assume that `\(f_{A \vert L}(a\vert l) > 0\)` for all `\(a\)` and `\(l\)` s.t `\(P[L = l] > 0\)`. + The IP weighting for individual `\(i\)` is `\(W^A_i = 1/f_{A\vert L}(a_i \vert l_i)\)`. + The IP weighted mean for treatment level `\(a\)` is `$$E[Y(a)] = E\left[\frac{I(A=a)Y}{f(A\vert L)}\right]$$` --- ## Equivalence of IP Weighting and Standardization + We will assume that `\(A\)` and `\(L\)` are discrete and `\(f(a \vert l) = P[A = a \vert L = l] > 0\)` for all `\(l\)` with `\(P[L = l] > 0\)`. + Use the iterated expectation formula: `$$E\left[\frac{I(A=a)Y}{f(A\vert L)}\right] = E_L \left \lbrace E_{A} \left\lbrace E_{Y}\left[\frac{I(A=a)Y}{f(A\vert L)} \Bigg\vert A, L \right]\right\rbrace \right\rbrace$$` `$$=E_L \left \lbrace E_{A} \left\lbrace \frac{I(A = a)E[Y \vert A, L]}{f(A \vert L)} \right\rbrace \right\rbrace$$` `$$=E_L \left \lbrace \frac{P(A = a \vert L) E[Y \vert A = a, L]}{f(a \vert L)} \right\rbrace$$` <!-- `$$=\sum_l \frac{E[Y\vert A = a, L = l]}{f(a\vert l)} f(a \vert l) P[L = l]$$` --> `$$= \sum_l E[Y\vert A = a, L = l] P[L = l]$$` --- ## Equivalence of IP Weighting and Standardization - This proof extends to continuous `\(L\)` by replacing the sum with an integral. - It doesn't extend to continuous `\(A\)`. We will talk more about continuous treatments in Part II. For now, we will always assume that the treatment has discrete levels. --- ## Causal Effects from Observational Data + None of our four identification conditions consistency, SUTVA, conditional exchangeability, and positivity require that our data is from a randomized trial. + However, these are much stronger assumptions in observational data. --- ## Consistencey - Consistency says: The outcome we observed for unit `\(i\)` ( `\(Y_i\)` ), who received treatment `\(a\)` is the same as the outcome we *would have observed* if we had intervened and set `\(A_i\)` to `\(a\)`. `$$A_i = a \Rightarrow Y_i = Y_i(a)$$` - In a trial with an intervention, consistency is almost tautological. + We *did* intervene and set `\(A_i\)` to `\(a\)`. - In an observational study we should think about if consistency is justified. + People may change their behavior if they receive an intervention vs. choosing a behavior independently. --- ## Conditional Exchangeability + In a trial, exchangeability is guaranteed by the study design. - The researchers control the assignment mechanism and therefore know all of the features which contribute to treatment probabilities. + In observational studies, treatment assignment occurs "naturally". - Identifying a set of variables to give conditional exchangeability requires assumptions and external information. - It may not be possible to measure all necessary variables. --- ## Positivity + In a trial, positivity is guaranteed by design. + In observational data, even if we know a set `\(L\)` of variables such that `\(Y(a) \ci A\ \vert \ L\)`, there may be levels `\(L\)` for which `\(P(A = a \vert L = l)\)` is close to or exactly zero. --- ## The Target Trial - Hernán and Robins argue that in order to identify a causal effect in observational data, we must have in mind a target trial that would identify the same parameter if it were feasible. - This includes clearly and specifically defining a hypothetical intervention. - However, that intervention doesn't necessarily need to be currently possible. --- ## Group Discussion Question - Design a "target trial" to test the question "Does getting a college degree increase earnings?" - Are there parts of the question you would modify? How/Why? --- ## Non-Modifiable Exposures - There are some features (e.g. race, sex, BMI) that are very hard to imagine modifying. - Another way to think about this is that race, sex, and body size are multi-faceted conditions. - These categories include multiple physical and social features. - In the case of race and sex, definitions may shift over time. - In some discrimination studies, there is a work-around: intervene on an observer's perceptions. - In admissions discrimination studies, the same applications are sent with different names. - In studies of housing discrimination, actors of different races view apartments. - We will come back to this issue later in the semester.